Welcome to Frank Takeaways. I'm Frank, writing the notes worth keeping from decades at companies like Slack, Etsy, and Google. I run a coaching practice dedicated to guiding leaders through the tricky stuff of building products and high-performing teams.

Join my referral program and earn 1:1 coaching sessions by sharing Frank Takeaways with others - start with just three referrals.

—

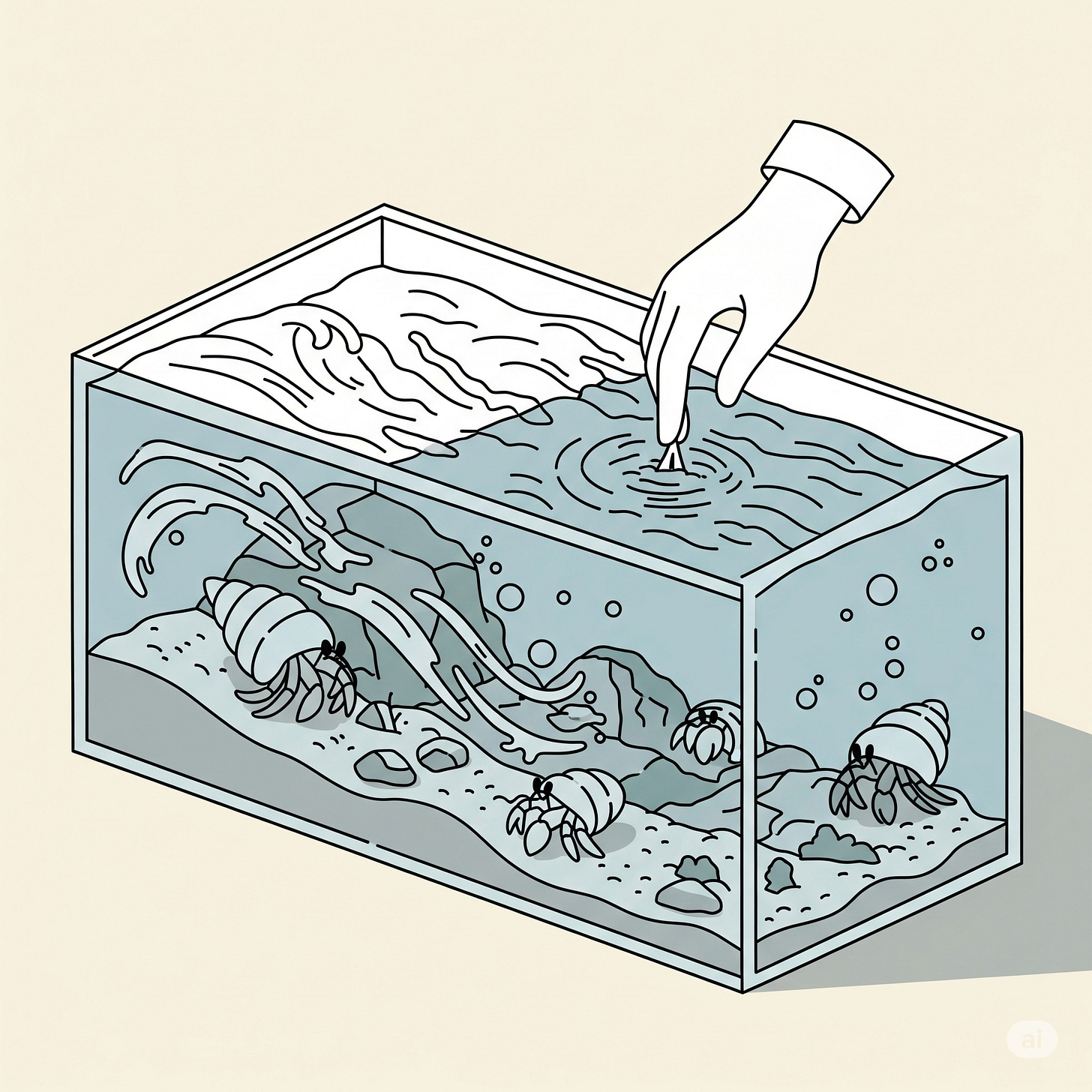

The woman on stage was talking about hermit crabs when I heard something that made me sit up:

"I would actually agitate them more. Today I'm the ocean, and today the ocean is dirty and mean!"

I'd never have been at this Pop-Up Magazine show if my former manager hadn't insisted. I was half-listening to Mary Akers explain how she'd accidentally become the world's most successful hermit crab breeder when that word — agitate — hit me like a wave.

That's when I understood what I'd been doing wrong as a leader for years.

After writing about where to position yourself (The Proximity Trap) and why to persist (The Good Stuff), readers kept asking: "But what do I actually DO when I get there?"

Mary had just given me the answer to a question I didn't even know I was asking.

There’s Something About Mary

She never meant to become a hermit crab breeder. She was an empty nester, pet-sitting for a friend, and ended up with a tankful of hermit crabs — each one stolen from a beach from halfway around the world, given a crabitat with a fluorescent gravel future.

When Mary realized these "throwaway" pets could actually live for decades — if cared for well — she decided to take responsibility. She built them a habitat the size of a grand piano and decided to tackle what no scientist had solved: breeding hermit crabs in captivity.

Her first attempts? Disasters. Mary hovered anxiously, adjusting water temperature by the degree, swapping foods at the first sign of distress. When her baby crabs died, she obsessed over what she wasn’t providing. More warmth? More food? More intervention?

But more wasn’t the answer. She was giving them performative care — the kind that soothes the caregiver, not the creature. What the crabs actually needed was something closer to the ocean itself: unpredictable, sometimes rough, always generative.

Mary couldn’t be God. She had to be the ocean.

Caring Isn’t About Comfort

Mary's discovery wasn't about crabs. It was about the gap between performative care and generative care — a gap I see in every leadership interaction.

In a recent coaching session, a VP was spiraling about her performance review with a struggling designer. "I've rewritten this feedback six times," she said. "I need to find exactly the right words so it lands perfectly. So they feel supported while understanding they need to grow."

I could hear that familiar tightness — the knot in your chest when you're trying to control an outcome while pretending you're just having a conversation.

"What if you didn't have to be perfect?" I asked. "What if you just had to create the right conditions?"

We've got it backwards. We think leadership means eliminating every bump, crafting every message so precisely that growth happens without discomfort. We perform care by hovering, adjusting, preventing pain.

But that's not how oceans work.

When Mary finally succeeded — when 204 baby crabs climbed from water to land in her makeshift ocean — it wasn't because she'd eliminated struggle. It was because she'd learned to create productive turbulence.

"I would actually agitate them more," she said, "move it around and give them, like, a low tide and a high tide."

That word — agitate — stops me every time. We spend so much energy trying to calm waters, and here's Mary deliberately churning them up.

The ocean doesn't apologize for its waves.

Molting Season: When Growth Means Shedding Our Shell

Like hermit crabs that must leave their shells to grow, I know what it feels like to be vulnerable in someone else's carefully constructed environment.

Years ago, my coach watched me spin for twenty minutes about a team conflict I couldn't resolve. I'd tried everything: one-on-ones, team exercises, process changes. Nothing worked, and I was exhausted from managing everyone's feelings about it.

Finally, she said: "What if this conflict is exactly what your team needs right now?"

I wanted her to give me a solution. Instead, she gave me a question that made my chest tight: "What are you afraid will happen if you stop trying to fix this?"

The answer came immediately: "They'll think I'm a bad manager."

"And then what?"

"They'll lose respect for me."

"And then?"

"I'll lose my job."

She let me sit in that discomfort. Didn't rush to reassure me or offer strategies. Just waited while I felt the full weight of trying to control something I couldn't control.

"What if," she said quietly, "your job isn't to eliminate their conflict, but to create conditions where conflict becomes productive?"

That conversation changed everything. Not because she solved my problem, but because she let me struggle with it in her presence. She was my ocean.

How to Be the Ocean: Creating Your Own Currents

Just as Mary learned to simulate tides and create productive turbulence, here's how to bring ocean-like leadership to your daily practice:

The Generosity of Early Honesty

One of my clients was tying himself in knots trying to explain why someone wasn't ready for promotion. I told him: "Close the door. Say she's not ready. If your boss wants to reopen it, she will."

The ocean doesn't hedge. The tide comes in.

A month before reviews, start the conversation. "You're phenomenal at visual design. I think you'd grow your influence if you could create the narrative around your concepts. What do you think?" Let them sit with that. Let them feel the pull of the current before the wave arrives.

This isn't cruel. It's honest. And honesty, delivered early, is generous.

Rhythms, Not Rescues

At Google, we wrote weekly "snippets": short notes on what we'd accomplished and what was next. Like the predictable rhythm of tides, these regular check-ins created a pattern of accountability. The discipline was uncomfortable, but the consistency helped us develop stronger habits — much like how Mary's crabs adapted to the rhythmic patterns of her artificial ocean.

That's ocean behavior: creating rhythmic patterns that shape growth through persistent, predictable challenge.

When I worked at a startup where the founder kept doing design drive-bys, I didn't try to stop him. I created a weekly design review forum. Same feedback, different container. Predictable tides instead of rogue waves.

The ocean doesn't eliminate chaos. It makes chaos productive.

Let Them Struggle (But Not Drown)

This is the hardest part. The part that costs something.

When you watch someone defensive about their work, every instinct screams to jump in. To soften the edges. To make it easier. Your throat tightens. Your hands want to move. You feel the urge to save them from the discomfort you've created.

Don't.

Mary put it perfectly: "Life for me, my lesson has always been just let go, Mary. Let them be crabs."

Your job isn't to eliminate their discomfort. Your job is to create conditions where discomfort leads to growth.

"You're phenomenal at visual design," you might say. "But you can't create the narrative around your concepts. How is that limiting your impact?" Then — and this is key — you let them sit in that discomfort. You agitate the water and wait.

Sometimes dirty, sometimes mean, always in service of growth.

But here's what nobody tells you about becoming the ocean: it changes your relationships.

When you stop performing care, some people feel abandoned. The ones who depended on your hovering, your endless adjustments, your willingness to absorb their discomfort — they'll push back. They'll tell you you've gotten "cold" or "demanding."

You haven't. You've just stopped being their anxiety management system.

People who've grown comfortable with your performative care will resist your generative care. They want you to keep managing their feelings instead of creating conditions for their growth.

The ocean doesn't personalize resistance. It just keeps being the ocean.

Tides and Time

Three months later, the VP texted: "Remember that designer? She came back with a plan. She's owning her development now."

That's what generative care creates.

But it requires getting comfortable with discomfort. Sitting with the physical sensation of watching someone struggle with feedback you could soften. Feeling your chest tighten when they push back and resisting the urge to explain yourself into oblivion.

When the urge to intervene grew too strong, Mary would whisper to herself: "Today I'm the ocean, and sometimes the ocean is dirty and mean." Not cruel, not capricious, but true to its nature — creating the conditions where life finds its own way to thrive.

By the end, Mary was breeding 700 crabs a year. She'd solved what trained scientists couldn't. Not through expertise, but through understanding something fundamental:

Love means letting go of control while maintaining conditions for life.

The hermit crabs that survived Mary's artificial ocean weren't the ones she saved. They were the ones who learned to save themselves in the environment she created.

That's the job. Not to eliminate struggle, but to make it generative. Not to prevent every wave, but to create the conditions where waves lead to growth.

Not to be God. Just to be the ocean.

—

Hear Mary tell it herself in Radiolab's Crabs All The Way Down.